Please Switch to Python

Or R. Or Anything. Just Not Stata, SAS, SPSS, or MATLAB.

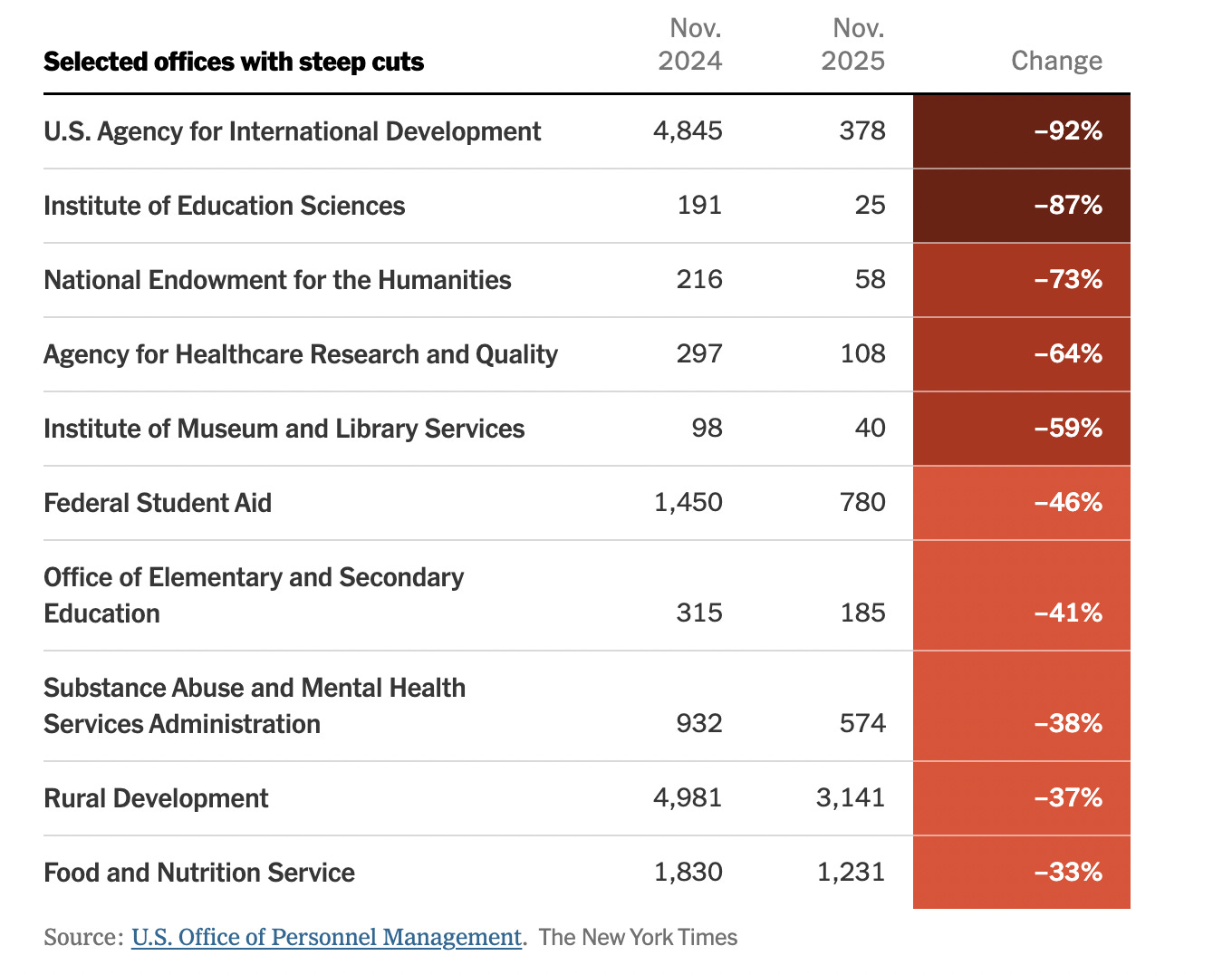

A few weeks ago, new federal workforce data came out from OPM. There’s a drag-and-drop tool for pre-built visualizations, but they also made over seven hundred monthly raw data files available for download. How? You click the download button. One at a time.1

This is fine if you only want a few files. But I wanted hundreds of them, for myself and to make available for other people with questions about this data. Downloading them manually means leaving no record of what you did, and doing it all over again if the data updates from Version 1 to Version 2. And if you make a mistake, are you going to realize it?

I didn’t pull it manually, but I still got the data. I’ll explain how in a moment. But first, some context.

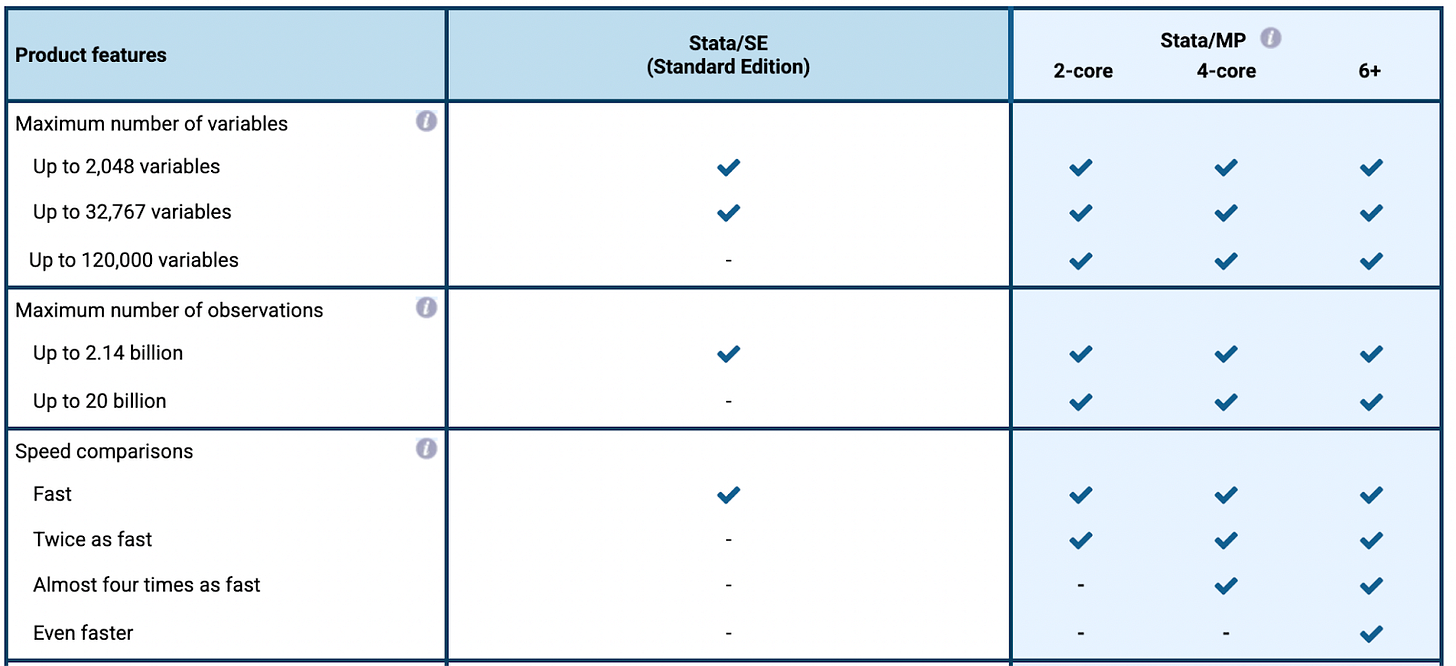

Stata, SAS, SPSS, and MATLAB are proprietary tools for statistical and mathematical analysis. You write code in them, though they have point-and-click interfaces as well. They’ve been around for decades, they’re taught in graduate programs, and a lot of people use them for analytical work.

When I say you should switch to Python from those tools, I’m using Python as a stand-in for something broader: open-source, general-purpose programming languages. R. JavaScript, whatever. The point here isn’t that Python is the One True Language2. You might be able to do everything you need in R, or you might, as is increasingly common, combine several languages.

But Python is the biggest and most general-purpose of these languages and the one I use most, so that’s what I’ll focus on. The argument is really: join the world where tools work together, you can build anything you want, and you can share what you built. AI coding assistance is making it much easier: the switching costs fell, so there’s even less reason to stay where you are than there was a year ago.

The OPM data

The data got released on a Thursday. By the time I could look at it, I’d already done my full-time job, run a meetup, and come home. I wanted to get this data up before the next morning, when I was hosting a call to share initial thoughts and go over what was available in the drag-and-drop tools vs. the raw data.

I also wanted to sleep.

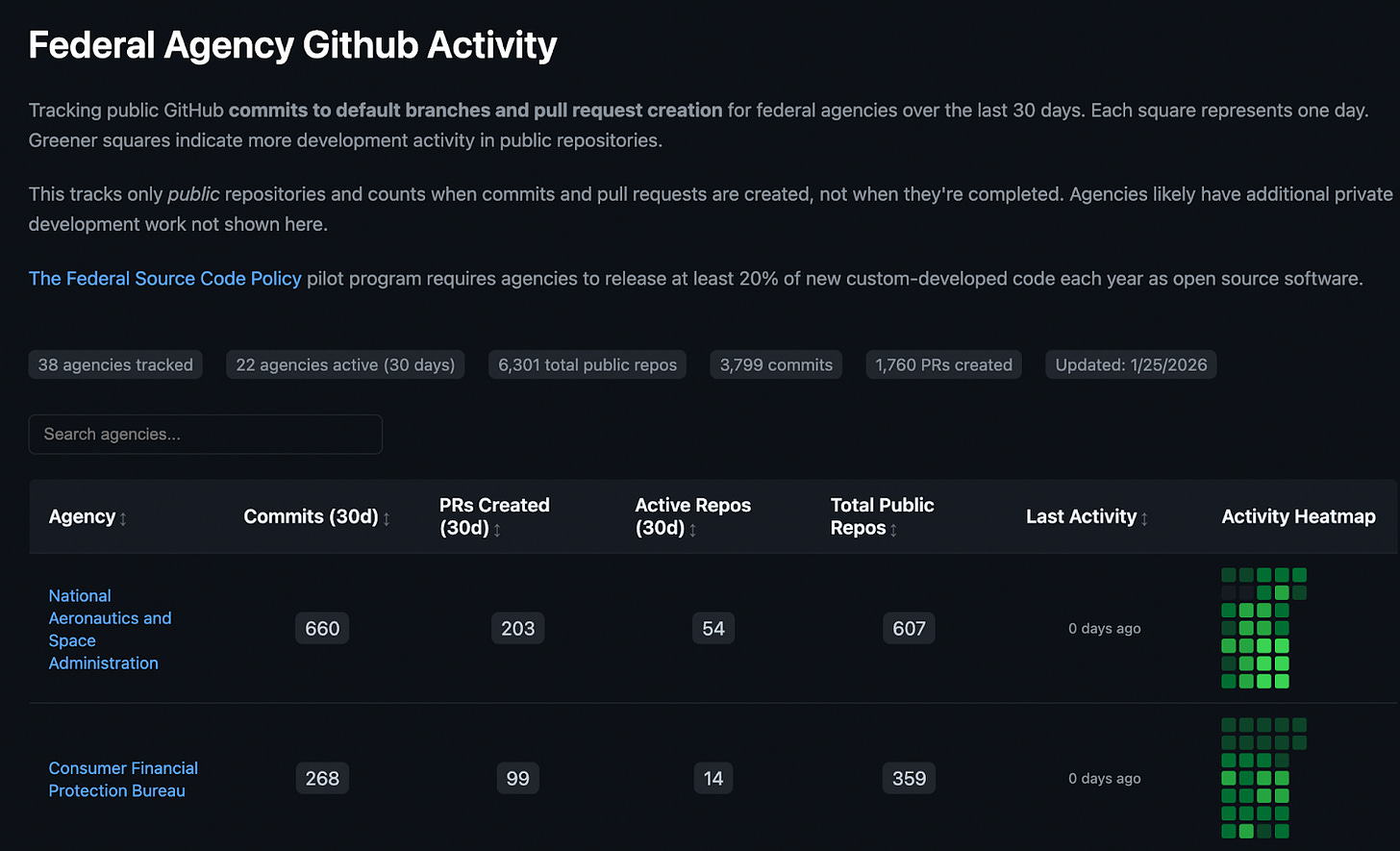

Because of how the OPM site loads, to download the data automatically, I needed something that could control a web browser. There’s a Python library called Playwright that does this beautifully. Anything you can do manually in Chrome, it can do with a script. A couple hours later, I had the files I needed, uploaded to Hugging Face where they can be easily downloaded or worked with in-place. I included a Jupyter notebook on GitHub demonstrating how to pull from Hugging Face and analyze the data. Claude Code helped enormously with every step of this.

Besides just the data, what does this get me? A workflow that’s transparent: every step is shared on GitHub. It’s repeatable. Other people can run it. I can build on it: when new versions come out, I can tweak the code. If I wanted, I could set up a GitHub Action to check daily for updates automatically and upload them to Hugging Face.

Last week, a reporter flagged a possible issue in the data. I replicated it, built a notebook reproducing the issue, and sent a link to OPM. They can run it themselves, because Google Colab makes that free for anyone. And they can follow what I did, because they have employees who know Python.

This is the infrastructure that exists. If you’re using Python.

You can’t do that in Stata, SAS, SPSS, or MATLAB

Browser automation? Stata can’t. SAS can’t. SPSS can’t. MATLAB’s answer is “call Python from MATLAB.”

Upload the data to Hugging Face? You’re going to be stuck using the GUI to drag-and-drop it.

Create a notebook anyone can run for free online? None of these allow that.

Put it on GitHub Actions to run automatically? Python comes pre-installed on GitHub Actions and can be run for free. None of these proprietary tools have that.

The pattern: even where these tools have some capability, it requires calling Python, or expensive licenses, or both. You only get the tools someone built for you—and those are narrower, because you’re a smaller and more specialized group.

What else opens up

Once you’re in Python, what counts as “data” expands dramatically.

Data no longer has to be a CSV or an API call wrapped up in a nice bow. It can be PDFs you found by automating Google searches. It can be Excel files someone built intending them to be gone through by hand, but you want years of them, you want to process their different formats and tabs, and you want a pipeline that grabs new ones and alerts you if they don’t match what you’re expecting.

Anything you can access online can be data, if you want it hard enough.

And then there’s what you can build to show your findings. I work in JavaScript now, and there are still plenty of websites I wouldn’t trust myself to build yet: anything with user authentication, a back end, payments. But if you’re a data person who wants sites with interactive visualizations? The JavaScript D3 library is what data journalists and data storytellers use. It’s the gold standard for communicating your results and letting other people play with your model or your findings.

And the sharing infrastructure isn’t just about code or results. It’s about data too. Hugging Face, git large file storage, all the tools software developers have been building let you easily share data. If your tools include Python, there’s a whole data-sharing ecosystem.

“I have no obligation to believe anything they write”

Researcher and statistician Andrew Gelman has this line I think about a lot: “The authors of research papers have no obligation to share their data and code, and I have no obligation to believe anything they write.”

This is how I feel about anyone trying to persuade the public of something while coding in languages that aren’t free to run. Are there people using Python who also don’t share their code? Sure, and that’s bad too. But if you’re using a proprietary language, you can’t share in a useful way even if you want to.

Part of this is audience. If you share a Stata .do file, only people with Stata licenses can run it. If you’re okay limiting yourself to the subset of your field who have licenses and know how to use them, fine. But if you want your work accessible to journalists, policymakers, researchers in adjacent fields, the public—you need tools they can use.

And part of it is structural. Users of proprietary statistical software are far less likely to share code at all because the tools don’t encourage it. Your code probably isn’t in a Git repo. It’s less likely to run end-to-end without manual steps. The workflow of “write reproducible code, put it on GitHub, let anyone run it” isn’t what these ecosystems were built for. Python and R communities developed around reproducibility and sharing. The proprietary tools didn't, so reproducibility in those ecosystems is the exception, not the norm.

Even if your code should never be public, the same problems apply internally: you can't run each other's work without licenses, can't easily hand it off, can't do anything outside this ecosystem.

The exceptions

Are there things you genuinely can’t do outside your proprietary software? Yes, but the list is short. SAS is still dominant for pharmaceutical submissions to the FDA, although there’s a growing R community. MATLAB's Simulink has capabilities for control systems hardware deployment that Python can't match. But Python now has PuLP for linear and integer programming, and PyTorch for machine learning—and Python has become the standard in ML.

And if you’re an economist cleaning data and running regressions, or even doing more complex statistical work3? You’re probably using it because you learned it in grad school and switching felt hard. Well, it’s not hard anymore. You can install Claude Code and ask it to translate your .do file into Python, run it, and compare the results. I’ve done this. If you can do the statistical analysis, you can figure out the migration as well.

And even where regulators demand a specific tool, or your analysis needs something not yet built in R or Python, you still benefit from using those languages. I used to work on a team where we had to use ACL, another proprietary analysis software, for compliance purposes: the auditors wanted the logs. So I wrote Python that generated the ACL code and ran both workflows in parallel, comparing results. Back then I didn’t know how to automate that comparison or have Python kick off the ACL, but now I do. The specialized tool can be the last mile, not the whole journey.

There’s a whole world out there

I know coders who prefer R but work in Python because that’s what the market asks them to do. I’ve rarely met anyone who learned Python or R after switching from Stata or SAS and said, “I wish I were still working in those.” Not everyone gets to choose their tools, but if you want to move to a job outside this ecosystem someday, or if you want to help your organization do better work, you need to know what else is out there.

There’s a learning curve, but it’s way less than it used to be. I haven’t written a line of code myself in months—Claude Code does it. The AI coding assistants are good enough now that “learning Python” increasingly means learning to think about architecture and workflows: how do you want data to flow, what should update automatically, how should pieces connect, what should you test? You no longer need to master syntax to work in these ecosystems.

And when you get there, I think you’ll like it. There’s data you haven’t been able to touch because it doesn’t come in a nice CSV. There are visualizations you haven’t been able to build because your tools don’t do interactive. There’s an entire infrastructure for sharing your work and your data that you’re not part of. Half of all developers use Python. Tens of millions of people, building tools for each other, for decades.

But maybe you’re reading this thinking: I don’t need browser automation. I don’t care about Hugging Face. I’m not trying to share anything with the public and I never want to make a website. Fine. But do you ever struggle to remember what you did six months ago? Do you have a 1,500-line .do file you’re afraid to touch? Do you copy-paste the same code between projects? Do you dread handing off work to a coauthor? Do you redo the same manual steps every time new data comes in?

General-purpose programming languages solve these problems too. Functions you can abstract out and reuse. Version control that tracks every change. Package managers that handle dependencies. The big flashy stuff—the browser automation, the sharing infrastructure—is what I’ve been talking about because it’s cool. But the boring stuff matters too, and it’s also better in Python.

The moat is disappearing

Unless you control access to unique data, the barriers to entry for analysis in your field have fallen. A grad student or policy analyst or random blogger with Claude Code can use your work and spin up something real with the same data you’re using, without being limited by their tools. And they can also access other data that you’re not able to.

The world where you can build a full pipeline in a weekend, pull from multiple datasets, test it, and share everything openly is here. The people who are excited about what’s becoming possible aren’t waiting.

This is not a complaint; I agree with the focus on drag-and-drop tools for the first iteration of the site.

If you hate Python but love Rust or Julia or C++ or lisp, I love you anyway and you’re not who I’m talking to and you can write your own blog post.

Very nicely communicated => “learning Python” increasingly means learning to think about architecture and workflows: how do you want data to flow, what should update automatically, how should pieces connect, what should you test? You no longer need to master syntax to work in these ecosystems.

Nobody is actually writing code anymore. So just have the AI write Python!