Hot Claude Summer

What I Built and What I Learned

When I left my federal government job in May, I wasn’t sure exactly what I wanted to do next, but I knew I wanted to build something useful. The prior months had been bleak. Projects I’d worked on felt fragile, like they might not exist after me. One day, I got a message that software I relied on was no longer approved. Then—poof—it was deleted from my computer.

Around that time, I decided to try Claude Code, the extension for Claude that runs in your development environment. I’d been using LLMs for coding since GPT-3.5, but apart from a short-lived experiment with GitHub Copilot, my workflow hadn’t changed: grab code from ChatGPT or Claude’s GUI, test it, iterate, paste back in. But I liked Claude, and suddenly I had the time to experiment.

There were some bumps, and it wasn’t good at everything, but going from GUI to Claude Code was as big a leap as when I first started using LLMs for coding. It let me build out what I wanted to build.

What I Built

What took shape this summer was a focus on making federal data more accessible. There’s a ton of really useful federal data out there that tells a lot of stories, but it’s not always the easiest to work with.

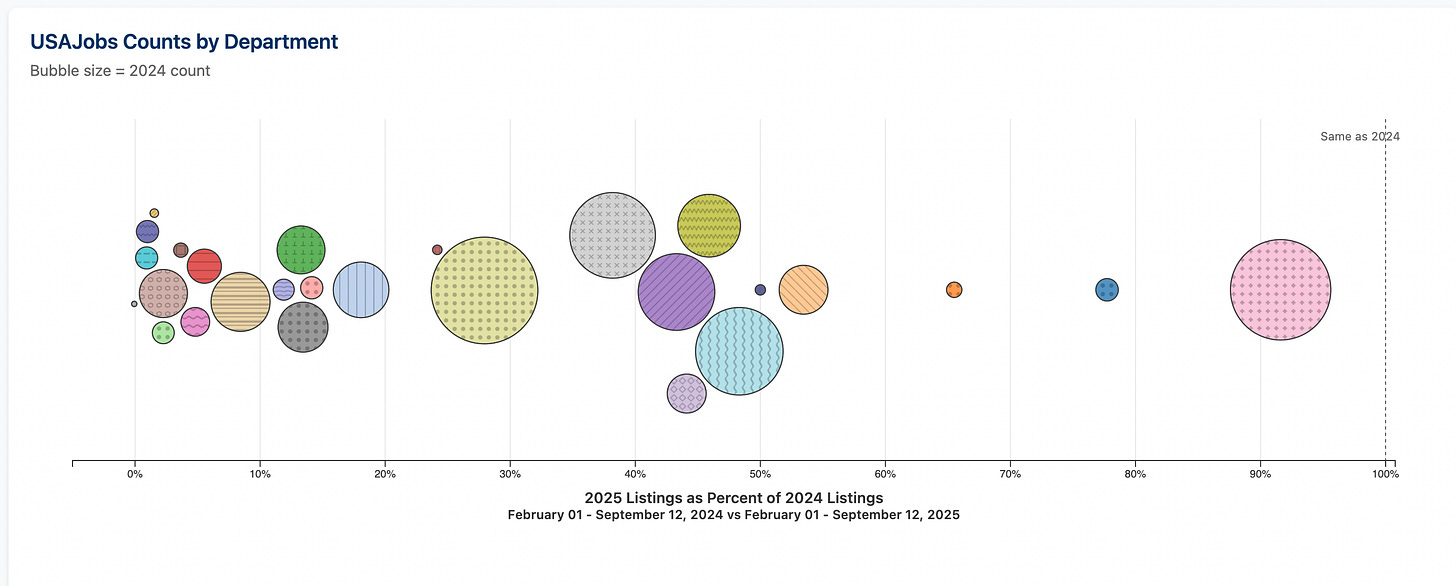

My biggest projects were with FedScope data, the official source on federal civil servants, and USAJobs data, which contains most federal job listings. I also worked with budget data—how much each agency is appropriated by Congress, and how much they’re obligating to spend—plus some public comment analysis and a demo for the Congressional hackathon that matches committee hearings with their YouTube videos.

Most of this work was data engineering—shifting data between locations and formats, like APIs, zipped text files, or Excel workbooks—and cleaning it up. Some was light web development: sites that might be interactive, but where everything runs in the browser, not on a back end or through a database. Claude Code helped in various ways:

When scraping questionnaires for federal job listings, switching from Selenium to Playwright took under half an hour and significantly sped up my scraping.

For matching the congressional hearings to YouTube videos, Claude suggested a package for getting YouTube metadata so I could stop using the very rate-limited YouTube API, and then implemented it.

Across all of this, Claude hardened pipelines with logging, error handling, and small things like caffeinate to keep my laptop awake overnight.

Not everything landed. I tried it for slides and data analysis, with much less success. It can draft slides, but I rewrite all of them. And its instincts for data visualization when asked to analyze a data set or even answer specific questions are terrible: overcomplicated charts, unreadable outputs, zero intuition for what the data is about.

Still, the sheer volume of what I was able to build—quickly, and in new domains—was different from anything I’d done before.

Bubble Charts and Bubble Math

Here’s one example of attempting something new. I needed to visualize budget data: agency, amount of funds appropriated, and the percentage of those appropriated funds which had been obligated.

Pre-LLMs, I’d have reached for the Python plotly package. If I was feeling ambitious, I might have tried Dash, the tool for making plotly figures into interactive dashboards. With LLMs, I might have worked in JavaScript, but I would still have felt constrained. With Claude Code, I started from a different premise and therefore a different question: I can build whatever visualization I want. What’s the best way to show the data?

That led to an interactive D3 bubble chart with multiple aggregation levels and filters responsive to user selections—built in one evening. And I don’t know JavaScript even a little. Initially, I also tried a two-color scheme for the inside and outside of the bubble using different colors for agency vs. subagency, but it was too busy, so I scrapped it. The luxury was being able to try and discard experiments so quickly.

A week later, I noticed some bubbles weren’t placed correctly on the x-axis. Bubble math is its own rabbit hole: balancing accurate placement on the x-axis against minimizing overlap. I ended up writing a grid search optimization for bubble parameters. It’s not good yet, and I may never fix it—but I wouldn’t even have thought to try before.

These are the problems I want to work on: showing complicated data clearly, not wrestling with syntax.

What Makes This Different

Claude Code lives in your environment. It sees everything—file structure, error messages, git state—and can act across it. That volume of context dwarfs what I’d copy-paste into a GUI.

Take minor refactoring: Claude can rename files, create folders, move things around, and update paths. I’d never bother doing that with an LLM if I had to copy and paste everything in. Or git errors: I used to debug them via Google and self-loathing. Now Claude fixes them, and sets up GitHub Actions I wouldn’t have attempted before. Suddenly, improvements are cheap.

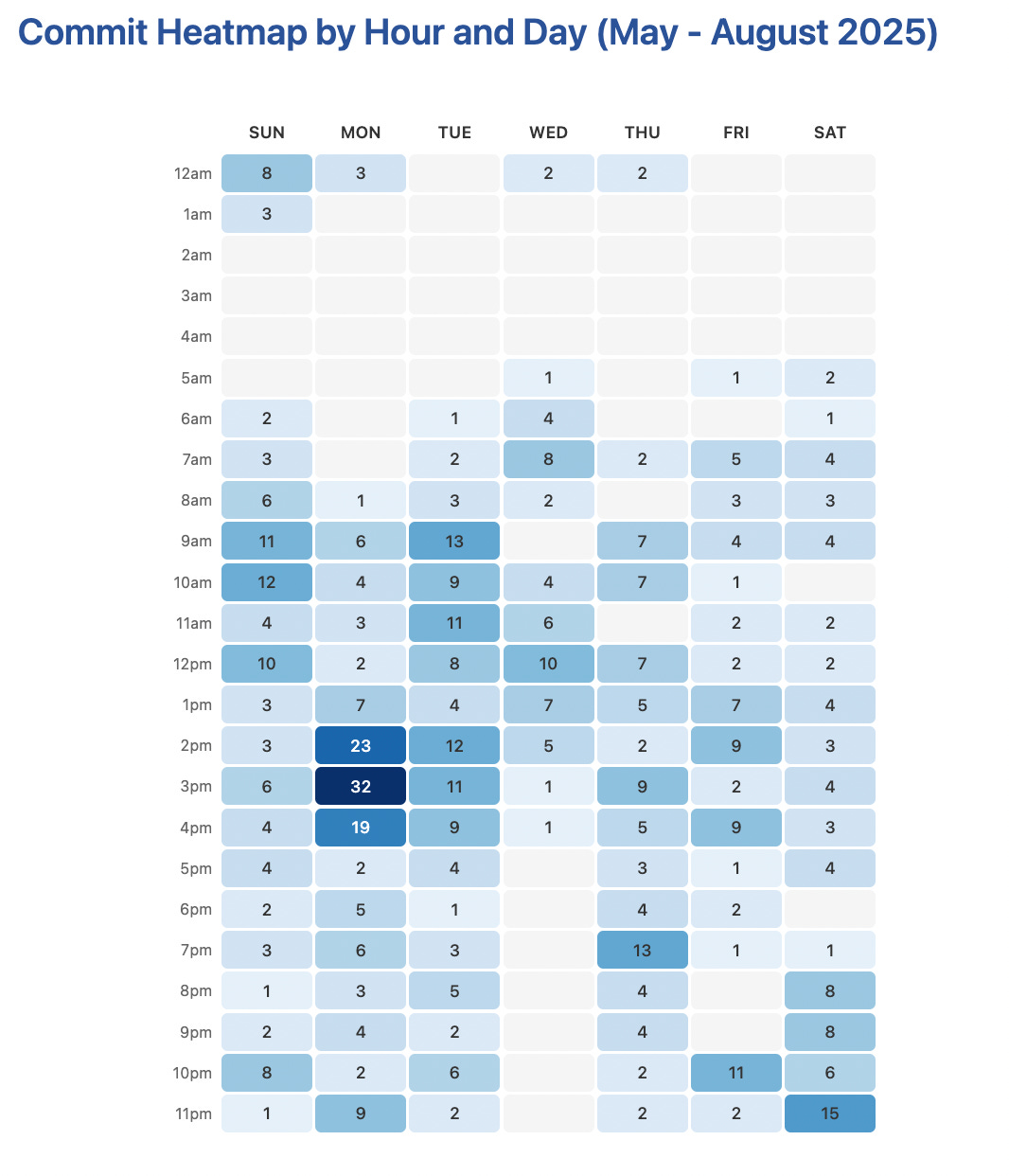

Another difference is that programming almost feels social. It’s more like coding with someone—like a rubber duck that talks back. So part of why I built more was that I spent more time doing it. I’ve always had the “I’ll be done debugging this soon” problem, where you look up and it’s an hour later. Claude Code made it worse because it made coding more engaging.

This heat map with my git commits—not all of them, but most—is an example of something I never would have spun up without Claude Code. But experimenting with visualizations of git commits for a blog post becomes totally reasonable when it takes 15 minutes.

Where It Fails

Like LLMs in general, Claude Code is strong on well-documented patterns—D3 charts, git parsing, GitHub Actions—but weak on data intuition and messy, real-world problems. I spent a day guiding it through a slightly novel dataset I already knew the answer to, just to see if it could reason its way there. It never got close, and it kept insisting it had solved it.

Budget data was another case: I went in circles until I realized the problem was that my obligations data had real dates, while outlays—the actual spending—was cumulative, a snapshot from whenever I pulled it. Claude Code was never going to figure that out.

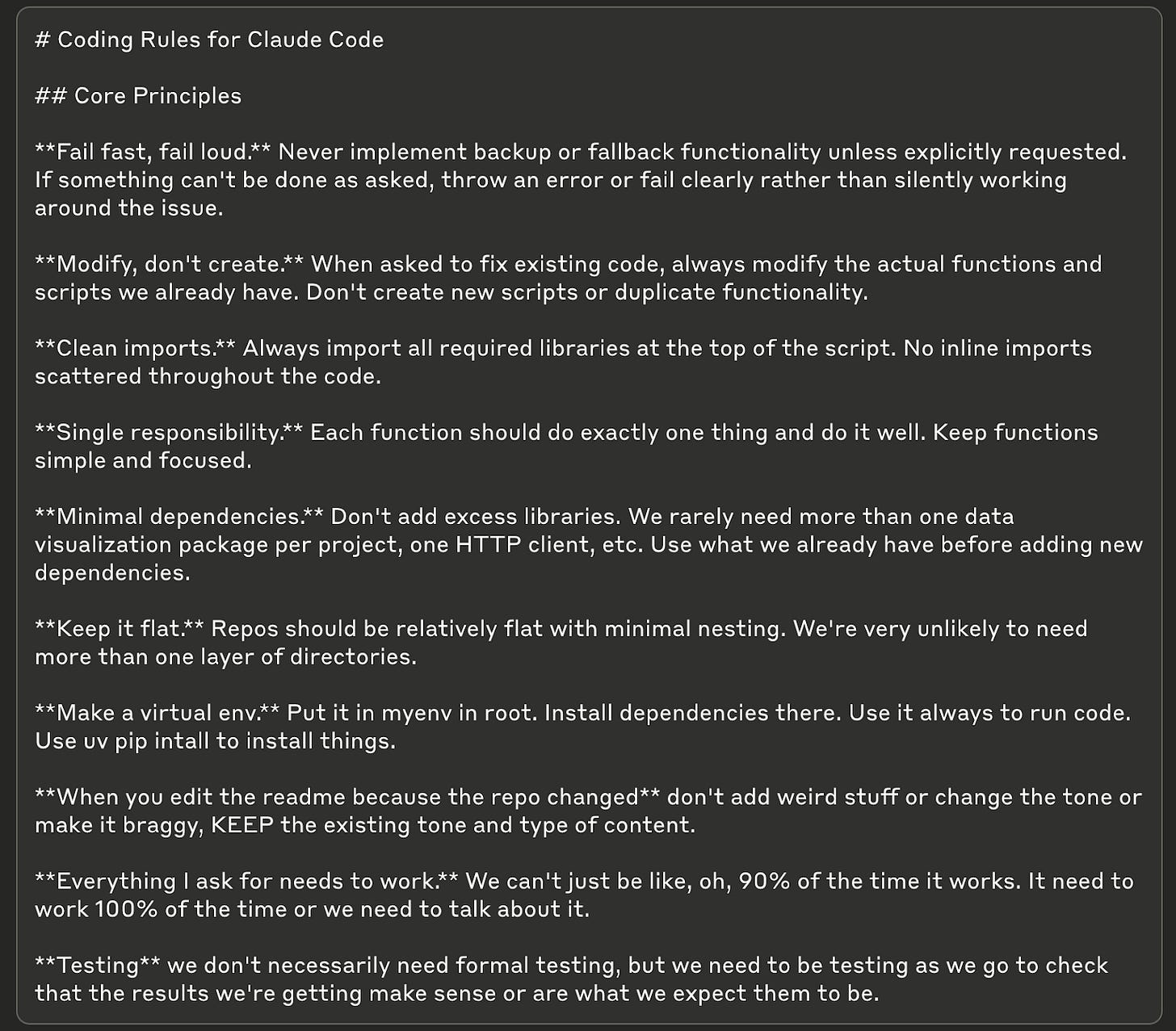

And even when it’s on the right track, it creates its own headaches: spawning new scripts instead of editing existing ones, sprinkling in try-catch blocks and functionality I never asked for and didn’t want.

The hardest failures came from deploying. I’d never launched websites before—let alone ones that updated automatically with new data—and every small break felt urgent, something I had to fix immediately no matter the time or what else I was doing. The problem was that building faster than I was learning how to test or maintain. Some of that was the speed Claude Code enabled; some of it was just side projects turning into tools. Eventually, I set up a more professional workflow for my sites with automated data updates: separate branches, and no more pushing to production without passing tests. Claude Code helped me get there, too.

What This Means

I’ve never liked low-code or no-code tools. They put you in a box—you can only build what someone else already implemented. Claude Code is the opposite. It opens boxes. It let me try frameworks, languages, and approaches I never would have touched before.

People sometimes cite the METR study to me, showing Claude Code didn’t help software developers much. I don’t know why I had such a different experience. My best guess is that it’s because in that study, developers were working on codebases they already knew well. For me, the value was mostly not that: Claude let me try things I otherwise wouldn’t have. Also, I’m not a software developer.

I am trying to retrain myself to slow down, look at the data more, and reinvest saved time in testing. It’s hard.

But even so: I’m grateful. I had this summer to choose what to build and put in the hours to do it. Now people email me asking for data. I start a new job soon, and I don’t know how I’ll keep it going. But that’s a good problem to have—and Claude Code is part of why I have it.