Make Things, Tell People

On side projects and finding work

I got my first job post-graduate school via a board game weekend1. Not a tech conference, not a networking event. I mentioned the research I was doing to another graduate student who matched me with someone looking to hire for very similar work.

Years later, with a lot more experience, I’m still currently not finding work through traditional application processes. When I left my job with the federal government in May, I decided it was going to be a better use of my time to build things than to send out resumes. I sent a few applications—Anthropic, still waiting to hear from you!—but by and large, it wasn’t something I even tried.

The short story: it worked out. I wound up with contract work I wanted, and it came entirely from a mix of side projects, networking via side projects, and previous coworkers. The mechanism is different now than it was in grad school—I have a network, and I can’t overstate how much that helped—but the pattern is the same as for that earlier job: make things, tell people.

And for that first job, I got lucky—I happened to be doing research someone was interested in. But after that, side projects were consistently what made the difference. Side projects let you make more of your own luck. You get to choose what you work on and what story you’re able to tell, instead of hoping your coursework or current job happens to match what someone wants and what you want to be doing. Side projects help in two ways—they can lead to opportunities through networking, but they also make your traditional applications much stronger when you do just apply.

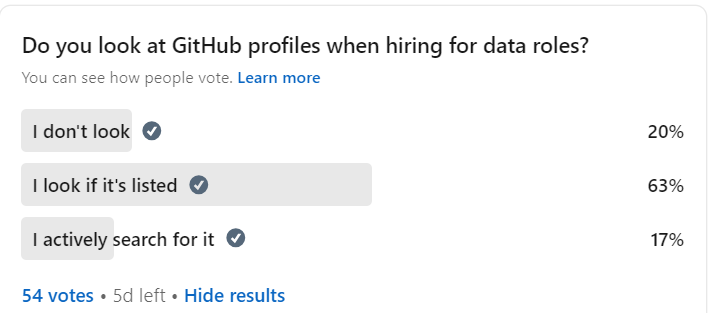

I write this because college students and people making career changes get in touch with me asking for advice, and I find myself being weirdly reluctant to tell anyone they should spend their free time on side projects, even though it’s what I do. And in a strong hiring market, traditional applications with coursework and internships work fine. But this is not that market. Managers are looking at hundreds or thousands of interchangeable resumes with the same coursework and the same ‘proficient in Python and SQL.’ You can’t retroactively change the school you went to or what your grades were, but you can build interesting, new things.

Why This Works

Side projects have a few built-in advantages that can be very hard to get otherwise, depending on your background:

Problem definition and solving. They let you figure out what problem is worth solving and how to solve it—as opposed to coursework, where you’re generally assigned problems that someone has figured out are solvable already. In this sense, this mimics work a lot more closely.

Clear individual contribution. They let you build something by yourself, so people can tell it was you, and in a way that you can make fully public—as opposed to work projects you’re not allowed to share and where it’s hard to tell what your role was.

Demonstrating genuine interest. Side projects are strong signal that you care about that topic.

Showing agency. You trusted yourself that something was worth doing and that you could do it. And then you did it.

These reasons also point to why some side projects work better than others. If you’re analyzing a data set that’s been done to death already, it’s harder to tell what you specifically contributed vs. took from someone else in terms of both the approach and the execution. It also doesn’t give you the chance to pick something that’s unique to you and your interests. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do that kind of side project—maybe you’re just doing this to learn a particular skill, in which case it doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks of it. But if you’re avoiding doing your own thing because you think every project has been done already and so you can’t possibly do anything new, this is false, and you absolutely can.

And all of these advantages matter whether you’re networking your way into opportunities or strengthening a traditional application.

How to Do It

Finding ideas

I spend a lot of time in places where people are talking about problems they have or topics they’re curious about. Data Science DC meetups, Signal chats where people talk about government tech, LinkedIn. When something really catches my attention, I start trying to figure out if there’s something small I can build to answer a question or solve a problem.

If you’re not in these spaces yet, start going to local tech meetups, free conferences, hackathons—whatever exists near you2. Listen to the talks. Pay attention to what problems people mention and what tools they use. For instance, you’ll see that GitHub isn’t optional even if your classes didn’t teach you how to use it properly. R is still used, but more frequently on teams where Python is as well. Polars and DuckDB are increasingly common. A lot of work involves LLMs. The tools people are using in their work and giving talks about are the tools you should be using in your side projects3.

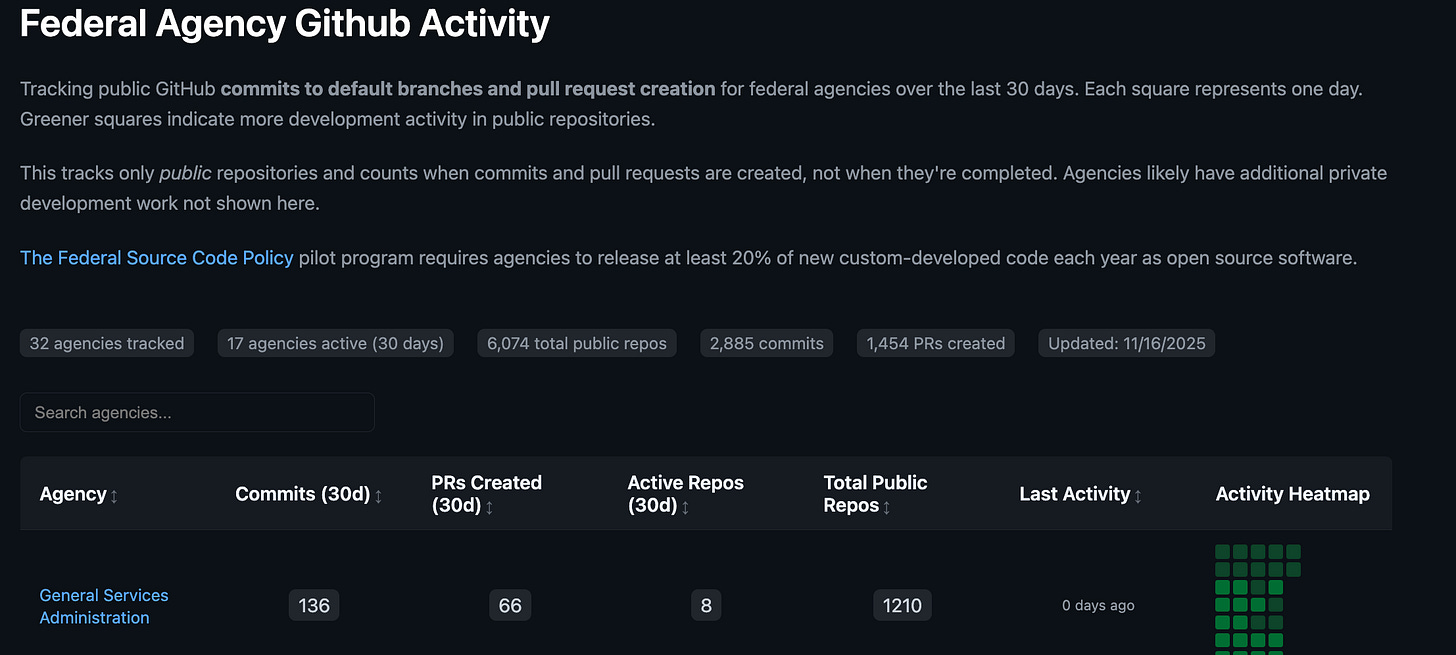

A recent project: I’d been hanging out in spaces where people talk about government open source, and I’d also recently worked with the GitHub API to pull commit data. I added those two things up and spent a couple evenings making a site that pulls data from government GitHub accounts to see what agencies are making code public. It wasn’t a big idea at all, it was just noticing two things I already thought about and connecting them.

That’s the pattern. Someone posts on LinkedIn. Or mentions something at a meetup. You read an article and think “wait, is that actually true?” And instead of just wondering about it, you go build something.

Telling people about it

Making the thing is only half of it. The other half is telling people.

I go back to the same spaces where I found ideas and share what I built. But also, I’ve messaged strangers to offer them data, and sometimes they say yes. I write blog posts so that later, when I’m talking to someone about that topic, I have something to send them.

When you show up in these spaces—especially if you’re early in your career—lead with what you’re working on or what you’re curious about, not with “I’m looking for a job”. “I was messing around with MCP servers and here’s what I built” is memorable and gives a sense of your interests and capabilities. “I’m looking for a data analyst role” does not.

And public events are just the first step. A lot of opportunities happen in private groups and conversations, but you’ll never meet the people who might invite you unless you engage with the public spaces first.

Telling people about it also includes putting it on your resume, along with links.

What You Get Out of This

I’m not saying this is how job hunting should work. And if you can find the job you want without doing any of this—the side projects or the networking—that’s great. I’m writing this because I don’t reliably know how to do that, so I do this instead, and I’m happy with how it’s worked out for me over the years.

Part of why I’m happy with it is that building things I find interesting is a lot less grim than sending out applications. It doesn’t feel like wasted time. And each project builds your skills—both the technical ones, but also the pattern of seeing a problem and making something that responds to it.

It was affiliated with a local university, and that’s absolutely doing some of the work in this story.

This is easier if you’re in a major city where these events exist and where there’s density of people in your field. If you’re not, you might need to be more deliberate—finding online communities and focusing more heavily on building a visible online presence through blog posts and LinkedIn.

This piece really made me think! Seriously, your "make things, tell people" approach is pure gold and so incredibly inspiring. As a teacher, I wonder what if our entire education system really leaned into portfolio-driven work over just CVs? Imagine the untapped talent it'd unlok!