GitHub: How To Tell Your Professional Story

This is a version of a talk I gave for posit::conf(2024).

I got my first data science job offer seven years ago this week, and I accepted it. It’s been a busy seven years professionally. I’ve held five different positions, reviewed approximately 500 resumes for various organizations, applied to give talks (including this one, and others where I wasn’t accepted), and selected speakers for the Data Science DC group that I co-organize.

The Importance of Professional Storytelling

Across these experiences, there’s a common thread: How do we effectively communicate about ourselves and what we bring to the table for potential employers or in other professional contexts? How do we interpret others’ stories? What’s the best way to do this?

The narrative I frequently try to convey about myself - and that I believe you’re likely trying to communicate as well - includes several elements:

Coding skills: As a data scientist, I write a lot of code. It’s a big part of what I do.

Problem-solving approach: When faced with a problem or set of requirements, I have a particular way of approaching it.

Technical practices and tools: My toolkit has expanded over the years. For instance, I recently learned Docker. That’s been great. Recommend!

Communication skills: This includes both my writing and speaking styles.

Challenges in Communicating Skills for Junior Candidates

But junior resumes are particularly difficult for communicating your skill set, more so than senior resumes. There are a couple of reasons for this:

Limited job experience in the field means fewer things you’ve built that you can talk about.

The wide variety of data science and data analytics programs lack standardization, making it challenging to interpret the skills gained from these programs.

For example, if you tell me you studied math as an undergrad or have a PhD in economics, I have a general idea of what that means. But if you studied data science, it’s not as clear. Even the same class across different programs can vary significantly in depth. So when I see this on a resume, it’s challenging to figure out what skills you’re actually bringing to the table.

Key Topics

In this talk, we’ll cover three main points:

Why GitHub is preferable to blogs, LinkedIn, or other platforms for communicating your skills.

How to select projects that effectively showcase what you can do.

Good development practices: what they are and how to implement them.

Why GitHub?

GitHub offers several advantages over other platforms:

Can show all your skills: GitHub allows you to demonstrate your actual code, problem-solving approach, and the tools you’re using. You might put a graph on a LinkedIn post, but on GitHub. I can see that the way you got to that graph was by writing functions, your code was modular, you abstracted it out. I can’t tell that just from seeing the graph. I’m also seeing how you communicate and how you approach a problem. I’m looking at your README file. I’m seeing what problem you were trying to solve and how you approached it.

Industry standard: Git is widely used in the industry, so familiarity with it is a valuable skill. Using Git is something you’re very likely to be doing at your next job. If you’re not using GitHub, you’re probably going to be using some kind of internal Git server, GitLab, or something else.

Free: Unlike personal websites, GitHub is free to use.

Lasting portfolio: Your GitHub repositories create a lasting portfolio that potential employers are likely to review. A year from now, when you’re applying for a job, that potential future employer is very unlikely to be reading your year-old LinkedIn posts. However, they really might be looking at your year-old repo.

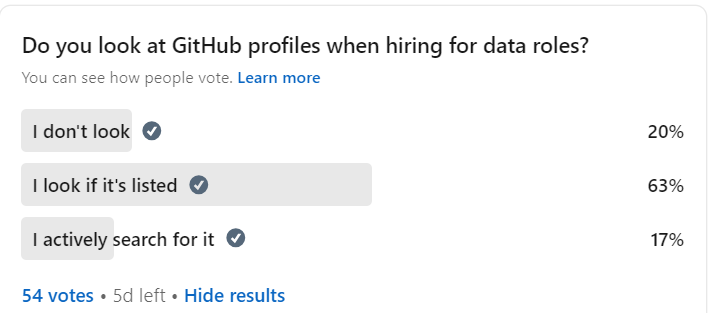

I did an informal survey on LinkedIn about this, and I asked people whether they looked at GitHub profiles when hiring for data roles. The majority said that they do look if it’s listed, and some people said they actively search for it. Very few people said that they don’t look.

Look, I’m on LinkedIn. I spend a lot of time on LinkedIn. I suggest you spend less time on LinkedIn than I spend on LinkedIn. I also have a blog, and I’m not going to tell you these things aren’t useful. But if you’re looking for the lowest hanging fruit in terms of spending a hopefully small amount of time in a way that has the greatest returns both to building your skills and showing off your skills, the answer is GitHub.

Working in Public

Before I was a data scientist, I was a PhD student. For a long time, even after I finished my PhD, I had this nightmare that somebody was going to ask to look at my code for my dissertation. Had they asked, we would have had problems. The first problem was that I had so many versions of Stata do-files, I couldn’t actually have told you which one created that final table or that final chart in my dissertation. I was not using version control. Problem two, the code was really bad. Embarrassingly bad.

I don’t have that fear anymore, and I want you to not have it either. Because now when I code, I approach it from the perspective that somebody is going to be looking at that code. I might look at it a year from now, and I want it to be useful. Or somebody else might look at it. And that completely changes how I code.

As much as possible, I put my stuff on GitHub from the beginning. That way, when somebody comes up to me and says (which does happen periodically), “Can I see your code for this?” I’m not stressing out. I’m not worrying about it. I send them the link to the repo. I call it a day. And that’s been incredibly powerful for me, and I want you to have that as well.

Selecting Projects

People ask me about how you pick a project, and the way I think about it is what are you trying to show that you can do?

In most fields, the way you get the skills to either move up internally at your organization or find a new job is somebody has to tell you, go ahead and do this. That is, you’re limited by what you’re allowed to do at your current job. For instance, if you need experience organizing very large conferences, you can’t do that on your weekends.

Whereas as a data scientist, and this has really helped me over the years, I don’t need to wait. If there’s a skill that I want because I think it’s going to be useful for me either moving up internally or at another organization, I can mostly just go get it. And that’s been really amazing.

So when you’re choosing your project, I would say the first thing to ask yourself is what skill am I either trying to get or just trying to show that I have. And I wouldn’t underestimate the current set of skills you have. For instance, if you’re junior in this field and you know how to use Git and your code is in functions and you write a README file, that’s actually really huge.

Next, interests. Let’s say you’re trying to show, for instance, I can get data from an API or I can do data viz or I can write functions. You can do that for any kind of data or any kind of interest that you have, and so why not pick something that you like?

And finally, scope. I mentioned this before. I really don’t think GitHub should be your part time job. You have jobs already, you have families, you have hobbies and friends, and all kinds of things that probably you would rather be doing. And so I would pick the smallest possible project you can do that either teaches or conveys what you’re trying to convey. You can always build something out further, but it’s harder to shrink something once you’ve already started. And one of the things you’re trying to show is that you can do something from start to finish.

Again, if what you’re trying to show is functions, modular code, a README file – if the only output of that is a table or chart, that’s fine. There’s a lot you can show with a very small amount of code. Scope it narrowly and then build more if you want to.

Good Development Practices

When people who are more senior say “good development practices,” it can sometimes sound like gatekeeping. It can sound like, “Here’s a hoop we want you to jump through,” or “There’s this thing that we spent the time and pain learning, and so we’re going to make you do it too.” That’s not how I want to come across, and I think that’s not how most people in this field want to come across.

Good development practices encompass:

Code that’s easy to run

Code that’s easy to build upon – for you or others

Code that’s easy to understand

That’s really it. Certainly, what that means is different across different projects. If you’re writing a package, that’s going to mean a whole lot of things that it’s not going to mean if you’re writing something for yourself or even for other people at your organization. But fundamentally, this is really all we’re talking about.

Here are some essentials for any repo you’re using to showcase your work:

Modular code: Use functions and potentially classes to organize your code. Each function does one thing, and you call it when you need it. You’re not repeating yourself.

All work in code: Avoid manual data manipulation outside your code. There’s not a part where you push your data to Excel, make some changes, and then read it back in.

Organized structure: Use appropriate folder structures and file organization. Maybe that means you have a subfolder for your results and a subfolder for your data. There are lots of different project structures out there.

Documentation: Include a README file and consider using docstrings. Your README file shows me what you did and why, and introduces all of it. I use docstrings more because GPT writes them for me now, so it’s faster - but no one is expecting you to have those.

Making sense: Ensure your code makes sense for the problem you’re solving. I should understand why you built what you did for the problem you were trying to solve. And maybe you find out midway through, “Actually, this isn’t how I should have solved it.” And you can put that in your README and say, “Here’s what I would do differently next time.”

Pin What You Want Them to See

When I was putting together this talk, I went to my own GitHub profile and I realized that my pinned repos, which are generally going to be the first thing somebody sees looking at your profile, were not actually the repos that I wanted pinned. That was a good lesson for me.

When I say people are going to look at your GitHub profile, I mean it. But generally, they’re not going to look at everything. They’re going to kind of breeze by and you want to make it as easy as possible for them to read the story that you want them to read.

Pin repositories that best showcase your skills.

Hide or remove repositories that don’t contribute to your professional narrative.

Ensure your profile tells the story you want potential employers to see.

What you want pinned, and it can be one repo or up to six, are the things that do the best job of communicating the skills that you’re bringing to the table, because that’s probably what people are going to click on. If you have recent commits, that’s the other thing that’s going to show up. But generally, your recent commits are going to be things you want somebody looking at. Whereas the things that GitHub decides it wants to pin really may not be.

Conclusion

Whether you’re new to GitHub or already have a profile, if you're sending out resumes with your GitHub profile on them, take the time to review and optimize your repositories. Think about the story you’re trying to tell about your code, communication skills, and overall professional package.

Again, you’re showcasing coding skills, problem-solving approaches, technical tools, and communication abilities. A GitHub repository can effectively tell this story.

Thank you for your attention. You can find more of my thoughts on my GitHub profile, LinkedIn, and Substack, where I’ve written about improving Jupyter notebook repositories and the broader implications of using Git as a hiring practice.

Came across this post randomly. It is great! I already updated my repo and will keep tinkering. Thank you!

When I'm interviewing for software roles, I rarely look, and when I do, I don't look deep. I look to get some ideas of problems that the candidate has solved - same with any job listed, or publications. Then I'm going to start with "tell me about project X", "how did you approach it", "what did you learn", "were you surprised by anything" and similar questions.

With respect to "what to put there" - don't put anything in front of an interviewer that you're not comfortable talking about. Also, you never know when you'll be interviewed by someone who is the expert in the topic.