Public Speaking: Getting the Basics Right

Last year, I gave a talk where I got something wrong. It had to do with a type of text analytics problem that I'd worked on back in 2018, then didn’t touch until GPT-3.5 came out. I didn't realize how easy to use some of the in-between methods were, and how little data they sometimes required until months after my talk, in which I had confidently proclaimed that the way to go for this problem type was to use an LLM.

Getting things wrong sucks. I have ideas about how to prevent this in the future. But there's no foolproof way to never be wrong!

But most of the time when I feel I’ve messed something up about a talk, it's not because I got something wrong, but because I didn’t manage some essential element of presenting well. And those are much more easily preventable.

This post will address three of those elements. These apply whether you’re speaking at a conference or meetup, or in a work context where you’re briefing out slides. They are:

1. Tell Us Why We're Here

2. Avoid Jargon

3. Make Clear Slides

I’ll conclude by discussing how you can try to get constructive feedback on your talk – and why this won’t automatically happen.

Tell Us Why We're Here

Andrew Gelman gave a keynote at the R NY conference in April, and I had no idea what he was doing or where he was going. There were no slides. I don’t know whether he got up there and riffed incredibly fluently for forty minutes about whatever he was thinking about that morning, or whether this was a carefully practiced talk he’d given multiple times.

Not being upfront with your audience about why you’re talking to them is a risky strategy. It can work for some people. I think it worked for Andrew: I found his talk compelling and I gave it my full attention.

But I’m not confident it would work for me, so I tell my audience why they're here in the first five minutes of any talk. And for talks over Zoom (where my audience will likely give me even less of a grace period before they tune me out and start answering their emails) I do it even sooner.

If you want the undivided attention of a room full of people, or the remote equivalent, give them a reason to pay attention to you. Tell them Why We’re Here.

Here are some examples of Why We Might Be Here:

My New Tool Solves Your Problem Better Than the Old Tools; Use It

We’re Going to Go Do a Thing, We Need Your Help, Here’s Why You Should Help Us

I’m Telling You How to Do a Process; If You Mess It Up, You’re Just Going to Have to Redo It

Having an agenda slide doesn’t take care of this. An agenda slide – and I usually have one of these – tells your audience what you’re going to be covering, but that’s not the same as why we’re here.

Having and communicating a reason why we’re here doesn’t just help me keep my audience engaged, it helps me organize the rest of my talk by tying the other parts of my presentation into the Why We’re Here. Because if I’m not communicating Why We’re Here in a sharp, well-defined manner, it’s likely because I haven't figured that out myself – and that’s going to show throughout my talk.

What if the answer to Why We’re Here is It’s a Mandatory Meeting So We Had to Be? That’ll get people in the (real or virtual) room, but it won’t necessarily get them listening.

Avoid Jargon

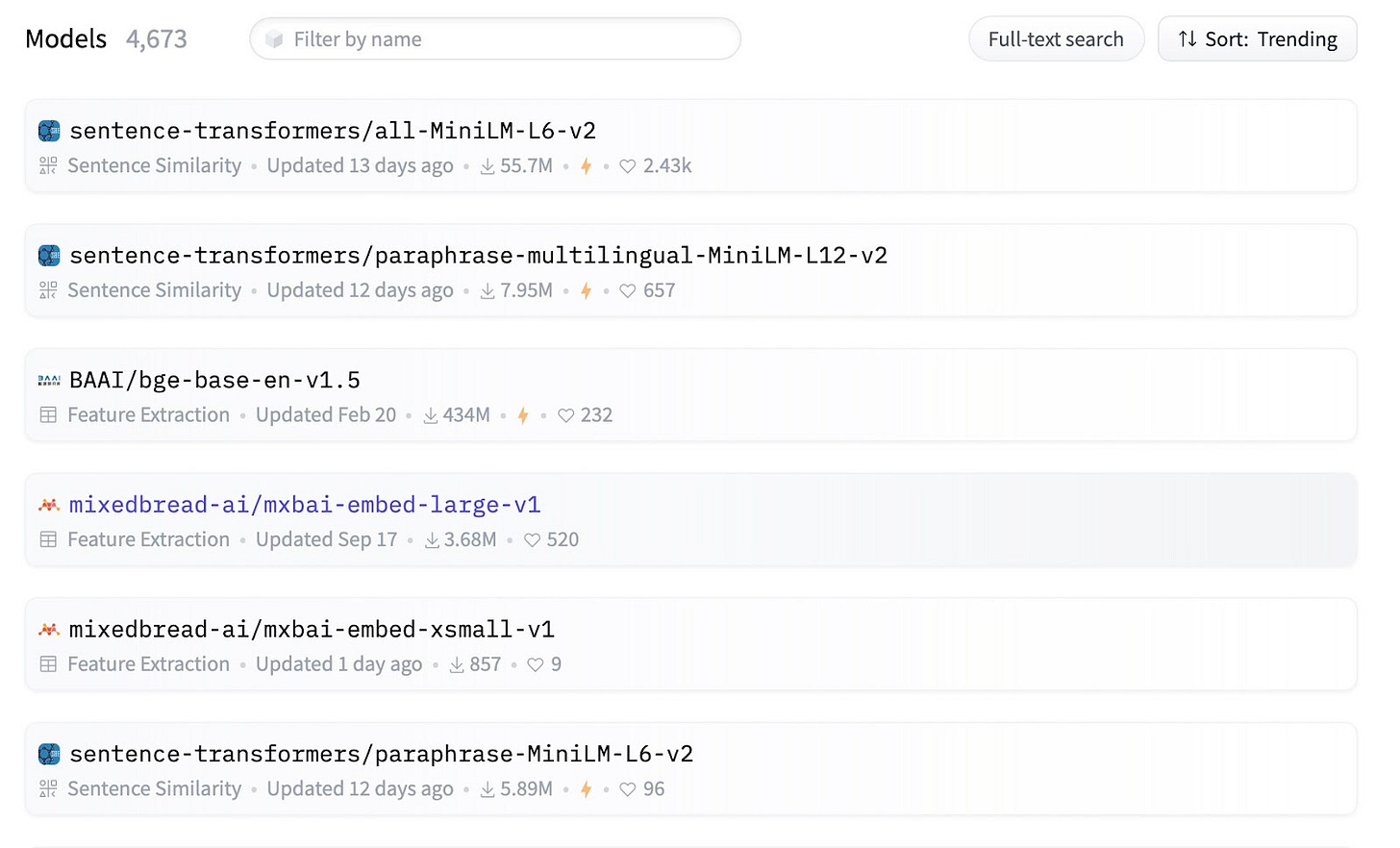

I love the phrase "dimensionality reduction." When we process text – for instance, for use in a RAG chatbot – we’re taking a body of text with a huge number of unique words in it, and we’re simplifying it to “reduce” it into a smaller set of variables via some type of language model. In this way, we go from a chunk of text to a vector of numbers, or a point in n-dimensional space, and we can then find the distance between two of those points – or, the representations of two text chunks – to see how similar they are in that space.

This is a great phrase and a useful concept.

It's also totally inappropriate to use in nearly any context, unless you’re going to put the work into explaining it.

So when I recently used it on a panel discussion, I immediately cringed. Because I know that using language your audience doesn’t understand is the fastest way to have them tune out.

To avoid jargon:

- Figure out what concepts your audience won’t be familiar with. If they’re not important, leave them out.

- For each concept that’s left, practice explaining it in plain language.

- Spell out and explain acronyms that are specific to your job or field!

As a speaker, my job is to get my message through, not to impress my audience with my vocabulary. And it’s better to err on the side of explaining a bit too much rather than incorrectly assuming your audience knows something.

Make Clear Slides

One of the things I like about using markdown to build my slides is that it nudges me to be selective about the amount of text on each slide. I use formatting at the beginning of the presentation that includes how big the font will be for every slide, and if I write too much, it overflows the slide rather than scaling the text, the way PowerPoint does. Yes, I could tweak the formatting when this happens – but I don't.

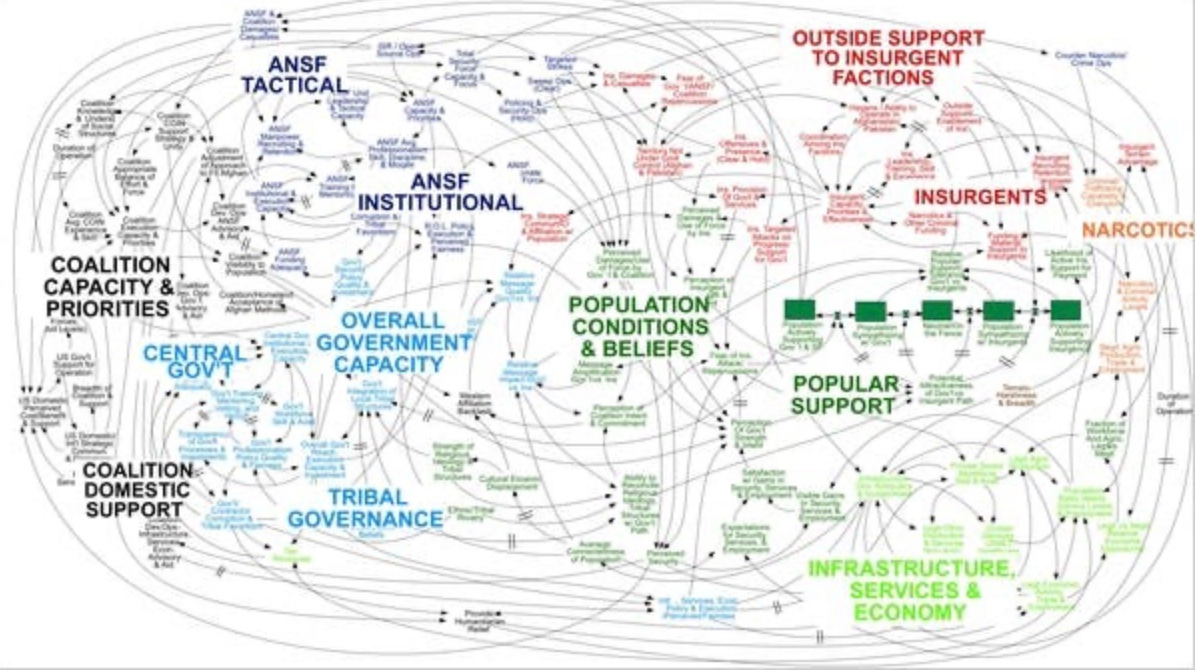

If you're using PowerPoint, you have to be more disciplined. And I think you should, because the biggest issue with slides is they have way too much text on them. When there’s too much text on your slides, people read your slides instead of listening to you. Or worse: the text is too small, so they’re trying to read it but they can’t, which is even more distracting!

Breaking up your slides is one way to avoid this; another way is to use text that appears sequentially. For instance, you talk through the first bullet point and then click to advance and show the next bullet point.

What if your slides are expected to have all the relevant content on them, because some people won't come to the briefing? Put text in your notes sections or in backup slides. You can also use backup documents: the related memo or paper with the full information in it, with the slides just containing the information that’s the most valuable to your audience.

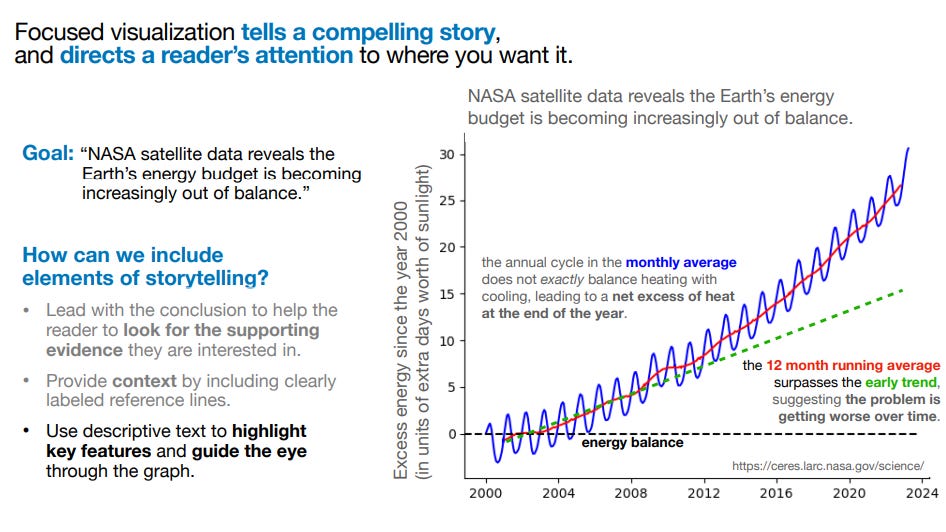

Figures are another element that are frequently done poorly on slides. If you're going to put a chart or graph on a slide, make it clear what your audience is supposed to be noticing. Maybe the title points it out – X Increased Since 2005. Maybe you circle or highlight what they're supposed to be noticing. Maybe you use multiple visual indicators to draw attention.

The slide below, from NASA Senior Graphics Designer & Data Visualization Specialist Alex Gurvich, provides an example of how to direct attention on a graph to the elements that you want your audience to notice.

Also, size still matters in graphs. And this is particularly unforgiving when you're giving Zoom talks, because your entire slide is just part of your viewer's screen. If your axis labels are too small to get read, make them bigger – even if you need to make slide-specific versions that are different from your publication versions.

You Cannot Rely on Feedback

I've done a lot of public speaking over the past year. I've spoken at three conferences, two in-person meetups, and one Data Mishaps Night. I spoke about federal hiring to OPM groups twice. I recently gave a brown bag, and was on a panel.

In none of these did I receive any unsolicited constructive feedback – and it's not because there wasn't plenty to give.

Why is this? Well, I also don’t typically give unsolicited constructive feedback, and here’s why:

I don’t want to assume I have something useful to say, or that the speaker wants to hear it.

Public speaking is stressful enough! I don't want to make it worse.

Speaking is often a volunteer experience. If someone has given up their time to give a talk, especially if it's for my event, I'm not going to tell them it could have been better!

Still, feedback is essential to improvement. So how can you get the feedback you need?

First, you can watch yourself on video. Note: I hate watching myself on video. And I suspect most people do. But it’s the easiest way to see what you’re doing.

For instance, I watched myself at Posit Conf and realized that I’m incapable of standing still for more than about five seconds. I find it horribly distracting to watch myself do this, and I wasn’t aware I did this until I watched myself.

Second, you can get feedback from people ahead of time.

For instance, if you’re speaking at an event, you can ask the organizers to look over your slides. You can ask them for general feedback, but you can also ask questions relating to the specific audience, like Is this too technical for the group? Will they be familiar with these concepts?

They might refuse. They might not have the time or feel like they have the expertise to answer your question – but they might say yes, and they’re unlikely to be offended by being asked!

For talks you’re giving at work, your ability to get feedback is going to depend on your specific organizational dynamics, but well-defined requests are more likely to get good results. This can include the type of feedback you’re looking for and when you need to hear back. For instance: If you have time in the next week to just spend a few minutes looking for jargon that might be confusing, I’d really appreciate that. Or: Do you have time for me to run a few slides? I’m trying to see if the opening makes sense and flows well into the rest of the presentation.

What about feedback from your actual attendees, after the fact? I think this is the hardest kind to get, but your chances are better if you ask someone ahead of time to pay attention to a specific thing. Like, Can you watch for if I’m loud enough or slow enough?

But even without feedback, you can hit the basics. Tell people why they're there. Don't use words they won't understand. Put less on your slides, and make what’s there clear. None of this guarantees you'll give a great talk, or even that you won't get things wrong. But you're less likely to look back on preventable mistakes.

Love this post! So many great points!