LLMs Already Outperform Data Scientists

Employers Just Haven’t Realized It

There’s a William Gibson line: the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed. I spend my days working with AI coding tools and I feel this acutely.

I held my last real data science job in 2023. Equipped with what exists now—I use Claude Code, but there are other similar tools like Codex and Cursor—I could have done that 40-hour-a-week job in under ten hours. And that’s with the meetings and the emails.

This isn’t a sustainable equilibrium, and at some point, employers are going to figure it out.

What I Did as a Data Scientist

Here are some of the kinds of tasks I did in that role as a data scientist:

Talking to people: briefing clients, managing small projects, getting information from subject matter experts who knew the data.

Creating documents: PowerPoints, short papers, code documentation.

Statistics: deciding what machine learning model to use, or how to solve problems involving distance minimization, or how to reduce the rate of flagging potential errors without causing more real errors to slip through.

Coding: writing Python and SQL to clean data and build reports – filtering, merging, aggregating. Figuring out how to get my code to post results in Teams or send emails. Making my code run faster on very large data sets. Figuring out how some API worked – for geocoding, or getting user stats for our dashboards – and using it. This was by far the biggest part of what I did.

By GPT-4, LLMs were already useful for coding and somewhat useful for the kind of statistics I was doing. At this point, they completely smoke me at this kind of work.

Here’s what I mean by this: Claude Code can find documentation better and faster than I can. It can synthesize information from multiple sources better and faster. It can write code, run it, read the error message, and fix the problem in the time it would take me to find a relevant Stack Overflow page and read a few responses. It can look at a problem I’ve never seen before and guess, usually correctly, how it’s supposed to work based on patterns it’s seen in a million other codebases.*

This is no longer just about taking a well-described query and generating the code for it.

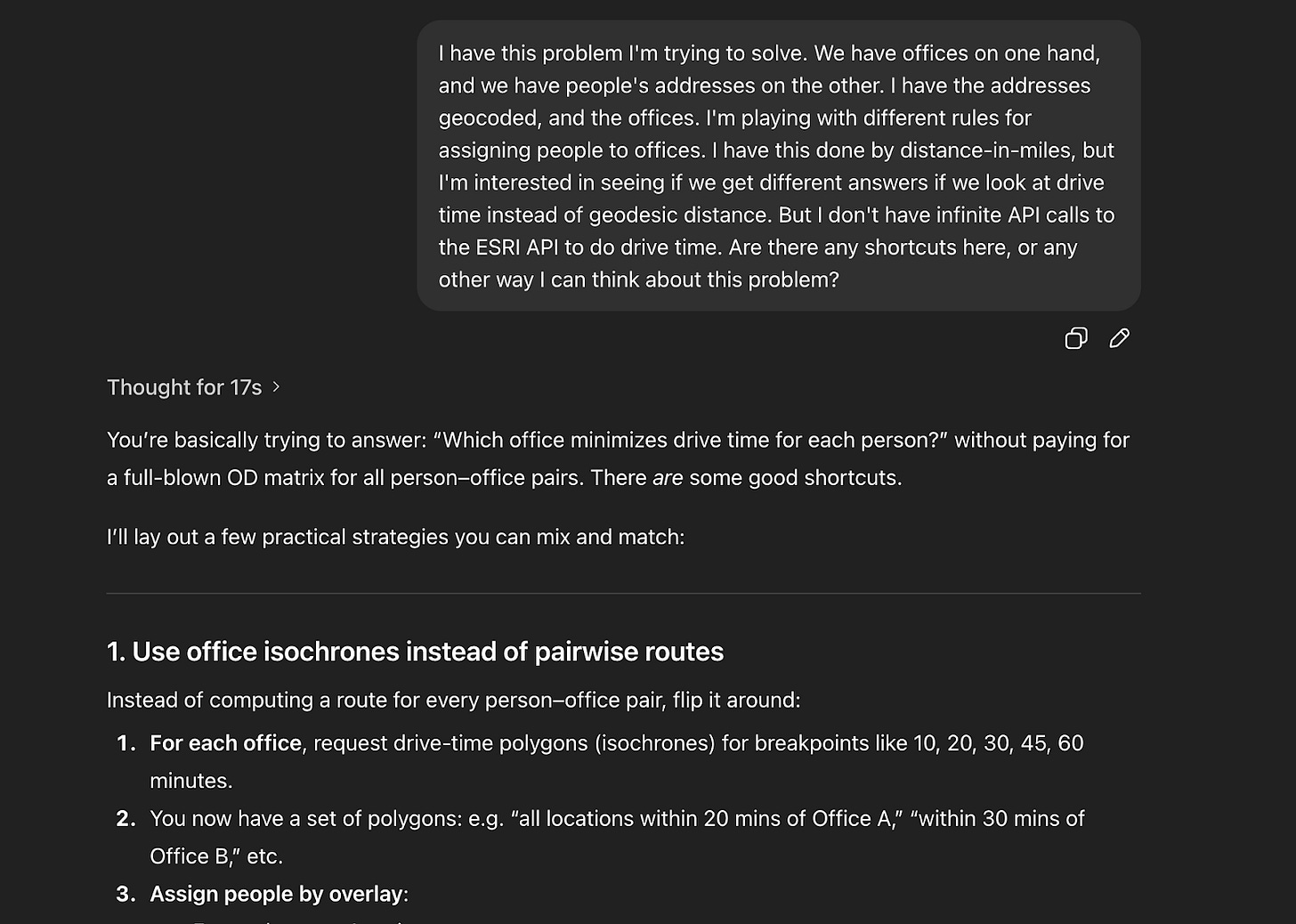

For instance, in 2023, I spent a few weeks trying to figure out the best way to do a specific geographical analysis, and I only got there because an engineer made a great suggestion at a brown bag I was giving. Now, that could have been one conversation with an LLM, and I would have gotten there much faster.

Or, there was the time when I was trying to figure out the best model to use for a machine learning problem–I had some ideas going in, but ultimately I got the answer from figuring out what outcomes I cared about and then systematically testing out different types of models to see how they performed on those outcomes. Claude Code could have done that with minimal input.

A lot of what separates pretty good data scientists from bad ones is tolerance for tedium. Willingness to read the documentation. Patience to debug. The discipline to write clean code instead of the spaghetti you might be able to get away with. Maybe you can’t become a great data scientist on the basis of that—I don’t think I was one— but being willing to just go in there and get the thing done no matter how annoying it was, and even better, get it done in a way that’s repeatable and clean and that someone else could understand—a lot of people can’t or don’t do that.

If you can automate that—and you can—then the gap between a good data scientist and a bad one gets a lot smaller. This job, as it was done, as I was doing it, becomes not just able to be done faster, but able to be done well by someone who previously wouldn’t have done a good job. It becomes far less skilled. The curiosity piece still matters—asking the right questions, really digging into the data, not believing your too-good-to-be-true results until you’ve sufficiently tried to disprove them—but even there, the barrier is lower than it was.

The Conversation I Keep Having

When I talk about this—for instance, in the context of how important it is to get government employees coding assistant tools, or how useful this has been for me—I get a couple kinds of pushback.

The first is “but it hallucinates”—as if that ends the conversation. Yes, LLMs make things up. So I deal with that. When I’m doing research, I ask for citations, including links and quotes, and I check them. For code, I write a lot more tests than I used to so I can verify the code is doing what I think it’s doing—which, like all the coding I do, is now much easier. There’s a learning curve, but this is not an unsolvable problem. And when people tell me LLMs aren’t reliable enough, I want to ask: compared to what? Have you seen the code humans write?

The second isn’t really an objection—it’s more that any conversation about LLMs being useful gets pulled into everything else. Doomerism. Environmental impact. Is AGI coming? Is there a bubble? (Maybe, but there was an internet bubble and we didn’t all stop using the Internet.) How awful are these tech bros?

I’m not dismissing all of those as unimportant, but they’re different questions from the one I’m trying to answer here, which is: what can these tools do right now, and what does that mean for work like mine and workers like me?

Most of the informed skepticism I hear comes from software engineers talking about enterprise software—large codebases, complex dependencies, production systems. That’s fair, or at least, I’m not the right person to argue this point because that’s not my domain.

But data science code isn’t enterprise software. We’re talking about smaller projects, often just one person. It’s not software that ships to users—it’s pipelines and reports that typically run on your machine or in a cloud environment your employer controls.

Because of that, the question of huge disruption in my field isn’t “are these tools perfect for all coding?” It’s “could someone much less skilled, armed with Claude Code, do better than the person currently in this job?” And having been a data scientist and worked with data scientists, I think the answer is often yes.

If you’re skeptical of this, I’d say: talk to your developer friends who are seriously engaging with these tools. The ones who are using Claude Code or Cursor all day, every day. Ask them what their work looks like now versus two years ago. Ask them if they’d go back. And try the latest models and tools yourself for research and data analysis. Treat it like any new technology, where you assume you’ll need to put some time into learning how to use it.

Where I Am Now

I was recently assisting a colleague who was newer to LLMs. They were trying to get a program to work and asking ChatGPT to help. They told it the software had errored, but they didn’t think to paste in the error message. It reminded me: I’ve been talking to these things constantly for years. Most people haven’t. The steps that have become automatic for me—what to ask, what context to give, how to check the output—none of that is obvious yet. And neither is it obvious what they can do.

That’s the gap. Not capability—we’re past that, at least in data science. It’s that most people haven’t learned how to use these tools, and most organizations haven’t figured out how to integrate them. The lack of labor market disruption so far is a matter of implementation, not capability. That’s what’s buying time.

Should this be about how data scientists are also becoming their own product managers with the help of LLMs?

Let the LLM be the Market fit tester and let the DS be the internal driver of new ideas that can be executed much more efficiently.